Diffusion and Resistivity #

Diffusion is a migration of particles that results in neutralization of any density gradients. Collisional processes affect the rate of diffusion. For example, particle random walks due to collisions can destroy plasma confinement.

For net energy gain in a confined fusion reaction, we must meet the Lawson criterion for a confinement time \( \tau \):

\[n \tau > 10^{14} \text{s}/ \text{cm}^{3}\]It is really hard to maintain a highly dense plasma for a long confinement time. Collisional timescales are very important for many plasma applications.

If we picture an ensemble of ions and electrons in a dense background of neutrals as a nonuniform gas, collisions result in diffusion. As the plasma spreads out as a result of pressure-gradient and electric field forces, individual particles undergo a random walk, colliding frequently with the neutral atoms.

Collision Parameters #

When an electron collides with a neutral atom, it may lose any fraction of its initial momentum, depending on the angle at which it rebounds.

First we consider a weakly ionized, unmagnetized plasma. If we consider only head-on collisions with perfect momentum absorption, the change in momentum is:

\[p_{e,f} - p_{ei,} = - m_e v - m_e v = - 2 m_e v = -2 p_{ei}\]Picture a volume in the plasma presenting an area \( A \) to an incoming electron flux \( \Gamma \). The thickness of the slab is \( \Delta x \). If the neutral atoms have density \( n_n \), and if we assume they have an effective collisional cross-section \( \sigma \), then the final flux emerging from our slab is

\[\Gamma^\prime = \frac{\Gamma A(1 - n_n \sigma \Delta x)}{A}\] \[\Gamma ^\prime = \Gamma (1 - n_n \sigma \Delta x)\]

We take the limit \( \Delta x \rightarrow 0 \) to turn it into a differential equation

\[\dv{\Gamma}{x} = - \frac{\Gamma n_n}{\sigma}\]If we solve it,

\[\Gamma = \Gamma_0 \exp(- n _n \sigma x) = \Gamma_0 \exp (-x / \lambda_m)\]where \( \lambda_m \) is the mean free path

\[\lambda_m = \frac{1}{n_n \sigma}\]Physically, \( \lambda_m \) is the distance required to reduce the incident flux by a factor of \( e \) due to collisions with neutral particles.

The mean time between collisions for particles with drift velocity \( v \) is given by

\[\tau = \lambda_m / v\]and the mean frequency of collisions is \[\tau ^{-1} = v / \lambda_m = n_n \sigma v\]

If we average over particles of all velocities \( v \) in a Maxwellian distribution, we get what we usually call the collision frequency \( \nu \):

\[\nu = n_n \langle \sigma v \rangle\]The collision frequency is a measure of the “number of mean-free-paths traversed in a unit of time.”

Diffusion in Weakly-Ionized Unmagnetized Plasma #

The fluid equation of motion is

\[m n \dv{\vec v}{t} = m n \left[ \pdv{\vec v}{t} + ( \vec v \cdot \grad) \vec v \right] = q n \vec E - \grad p - m n \nu \vec v\]Assuming we can work out a collision frequency \( \nu \) consistent with the fluid equations, then we assume \( \nu \) is constant in order to make the equation of motion useful.

For small \( \vec v \) or large \( \nu \), \( \dv{\vec v}{t} \approx 0 \), so

\[\vec v = \underbrace{\frac{q}{m \nu}}_{\equiv \mu} \vec E - \underbrace{\frac{k_b T}{m \nu}}_{\equiv D} \cdot \frac{\grad n}{n}\]where we call \( \mu \equiv \frac{q}{m \nu} \) the particle mobility and \( D \equiv \frac{k_b T}{m \nu} \) the diffusion coefficient. The flux is

\[\Gamma _\alpha = n \vec v_\alpha = \pm \mu_\alpha n \vec E - D_\alpha \grad n\]If we have uncharged particles, we just get Fick’s law for gas particles

Fick’s Law

\[\Gamma = - D \grad n\]

Ambipolar Diffusion #

Diffusion is necessarily always directed against the density gradient, but in plasmas the net flux is not necessarily given by \( \grad n \). The electrons and ions will eventually diffuse to the walls of their container and decay over time. They will have to diffuse at equal rates in order to maintain charge neutrality. Consider the continuity equation

\[\pdv{n_\alpha}{t} + \div \Gamma_\alpha = 0\]If \( \Gamma_i \neq \Gamma_e \), then \( n_i(t) \neq n_e(t) \), so we must have \( \Gamma_i = \Gamma_e \) to maintain charge neutrality.

\[\begin{aligned} \Gamma &=& \mu_i \frac{D_i - D_e}{\mu_i + \mu_e} \grad n - D_i \grad n \\ & = & \frac{\mu_i D_i - \mu_i D_e - \mu_i D_i - \mu_e D_i}{\mu_i \mu_e} \grad n \\ & = & -\frac{\mu_i D_e + \mu_e D_i}{\mu_i + \mu_e} \grad n \end{aligned}\]This is Fick’s law with a different diffusion coefficient, called the ambipolar diffusion coefficient:

\[D_a \equiv \frac{\mu_i D_e + \mu_e D_i}{\mu_i + \mu_e}\]Considering that the mobility of the electrons is much higher than that of ions,

\[D_a \approx D_i + \frac{\mu_i}{\mu_e} D_e = D_i + \frac{T_e}{T_i} D_i \approx 2 D_i\]Ambipolar Diffusion coefficient

\[D_a \approx 2 D_i\]

Diffusion in Weakly Ionized, Weakly Magnetized Plasma #

The rate of plasma loss by diffusion can be decreased by the presence of a magnetic field. Consider a weakly ionized plasma in a magnetic field pointing in the \( \vu z \) direction. Because \( \vec B \) does not affect motion in the parallel direction, charged particles will move along \( \vec B \) by diffusion and mobility according to:

\[\Gamma_\alpha = \pm \mu n E_z - D \pdv{n}{z}\]If there were no collisions, the particles would not diffuse at all in the perpendicular direction - they would continue to gyrate about the same line of force. There are particle drifts across \( \vec B \) because of electric fields or gradients in \( \vec B \), but these can be arranged to be parallel to the walls. For instance, in a perfectly symmetric cylinder, the gradients are all in the radial direction, so the guiding center drifts are all in the azimuthal direction and would be harmless for containment.

When there are collisions, particles are able to migrate across \( \vec B \) to the walls along the gradients, by a random-walk process. When an ion, say, collides with a neutral atom, the ion leaves the collision traveling in a different direction. It continues its gyro orbit along the magnetic field, but its phase has changed discontinuously, and the guiding center shifts position. (The Larmor radius can also change, but let’s suppose that the ion does not gain or lose energy on average).

As before, let’s write down the perpendicular component of the fluid equation of motion

\[m n \dv{\vec v_\perp}{t} = \pm e n (\vec E + \vec v_\perp \cross \vec B) - k_b T \grad n - m n \nu \vec v = 0\]where we’ve assumed that the plasma is isothermal and that \( \nu \) is large enough for the \( \dv{\vec v_\perp}{t} \) term is negligible. Working through, we get

\[\mu_\perp = \frac{\mu}{1 + \omega_c ^2 \tau^2}\] \[D_\perp = \frac{D}{1 + \omega_c ^2 \tau ^2} \]

In this context, we call \( \omega_c \tau \) the Hall parameter. If \( \omega_c \tau \gg 1 \), then

\[D_\perp \approx \frac{k_b T}{m \nu} \frac{1}{\omega_c ^2 \tau ^2} = \frac{k_b T \nu}{m \omega_c ^2}\]For comparison with parallel diffusion,

\[D = \frac{k_b T}{m \nu} \]the dependence on the collision frequency has reversed.

If we disregard numerical factors, we can write the parallel diffusion coefficient as

\[D \sim v_t ^2 \tau \sim \lambda_m ^2 / \tau\]This shows that diffusion is a random walk process with step length \( \lambda_m \), as we said. For perpendicular diffusion in a partially magnetized plasma,

\[D_\perp = \frac{k_b T \nu}{m \omega_c ^2} \sim v_{th}^2 \frac{r_L ^2}{v_{th}^2} \sim \frac{r_L ^2}{\tau}\]This shows that for perpendicular diffusion the particle guiding center takes a random-walk process with step length on the order of the Larmor radius \( r_L \), rather than the thermal collision path \( \lambda_m \).

Collisions in Fully Ionized Plasma #

In a fully ionized plasma, all collisions are Coulomb collisions (as opposed to momentum-conserving head-on collisions with neutrals as discussed earlier).

There is a distinct difference between collisions between like particles (ion-ion or electron-electron collisions) and collisions between unlike particles (ion-electron). If we consider two identical particles with equal mass colliding, then the center of mass of the system is will not change over the collision process, so that the particles emerge with their velocities reversed. This means that like particles simply interchange their orbits. The worst that can happen is a head-on collision, in which the velocities are changed by \( 90^\circ \) in direction. Even in this case, the center of mass of the two guiding centers remains the same. For this reason, collisions between like particles give rise to very little diffusion.

When unlike particles collide, the situation is very different. The worst case is now a \( 180^\circ \) collision, in which the particles each emerge with their velocities reversed. Since they must continue to gyrate about the lines of force, both guiding centers will move in the same direction. Collisions between unlike particles give rise to diffusion. Because of the mass difference between electrons and ions, the physical result is a bit difficult to picture, but because of the conservation of momentum in each collision, the rates of diffusion are the same for ions and electrons.

Plasma Resistivity #

The fluid equations of motion including the effects of charged-particle collisions may be written as

\[m_i n \dv{\vec v_i}{t} = e n (\vec E + \vec v_i \cross \vec B ) - \grad p_i - \grad \vec \Pi_i + \vec R_{ie}\] \[m_e n \dv{\vec v_e}{t} = -e n (\vec E + \vec v_e \cross \vec B ) - \grad p_e - \grad \vec \Pi_e + \vec R_{ei}\]

where \( \vec R_{ie} \) and \( \vec R_{ei} \) represent the momentum gain of the ion fluid caused by collisions with electrons, and vice versa. Conservation of momentum requires

\[\vec R_{ei} = - \vec{R}_{ie}\]We can write the \( \vec R_{ei} \) terms in terms of the collision frequency:

\[\vec R_{ei} = m n ( \vec v_i - \vec v_e) \nu_{ei}\]Physically, we expect \( R_{ei} \) to be based on Coulomb collisions, so it should be proportional to \( e^2 \). It should also be proportional to the density of electrons \( n_e \) and the density of scattering centers \( n_i \). And finally it should be proportional to the relative velocity of the two fluids:

\[\vec P_{ei} = \eta e^2 n^2 (\vec v_i - \vec v_e)\]Comparing the two, we can write down the specific resistivity \( \eta \) as

\[\eta = \frac{n e^2}{m \nu_{ei}}\]Coulomb Collisions #

Now, we need to know the collision frequency for an ionized plasma. Collisions due to the Coulomb force are long-range, unlike the billiard ball collisions with neutrals. We can still estimate an order-of-magnitude collision cross-section.

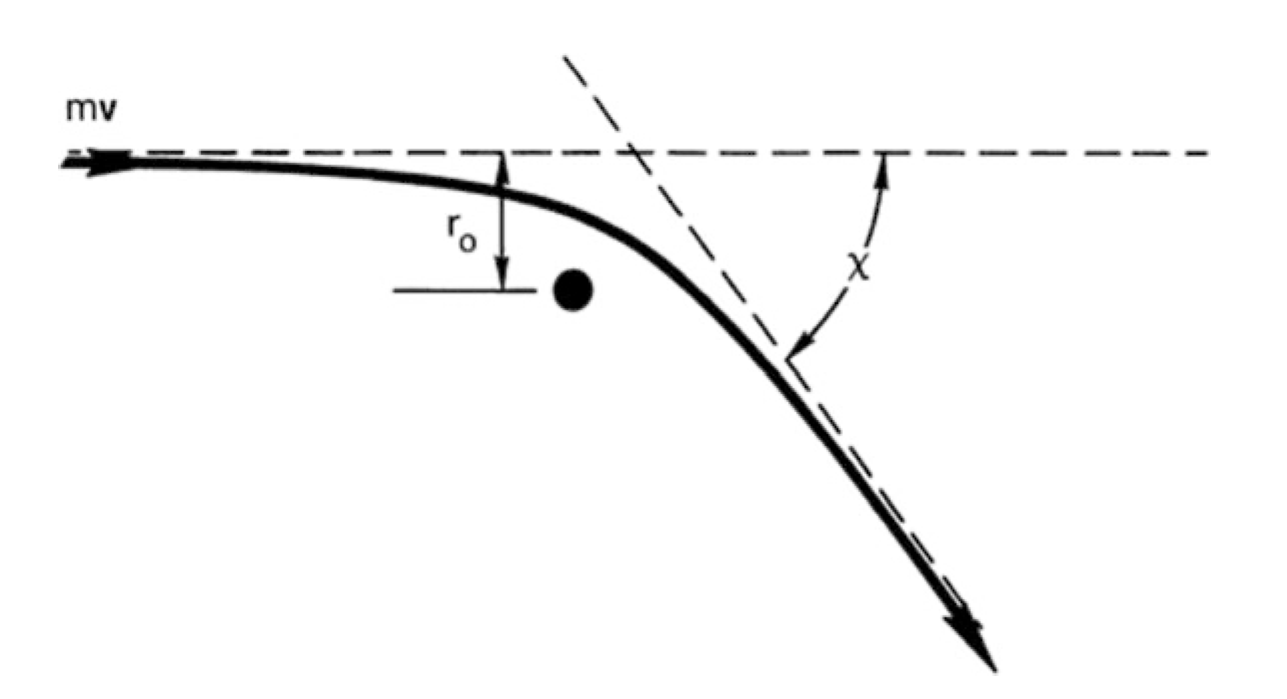

We define the impact parameter \( r_0 \) as the distance of closest approach for a collision which deflects over an angle \( \chi \):

The Coulomb force

\[F = \frac{e^2}{4 \pi \epsilon_0 r^2}\]is the force felt by the electron near the ion. The transit near the ion takes roughly a time \( T \approx r_0 / v \), so the change in momentum is nearly

\[\Delta (m v) = |F T| \approx \frac{e^2}{4 \pi \epsilon_0 r_0 v}\]If we consider only large angle collisions \( \chi \geq 90^\circ \), then \( \Delta m v \approx m v \) and

\[\Delta (m v) \approx m v \approx \frac{e^2}{4 \pi \epsilon_0 r_0 v}\] \[r_0 = \frac{e^2}{4 \pi \epsilon_0 m v^2}\]

The cross-section is

\[\pi r_0 ^2 = \frac{e^4}{16 \pi \epsilon_0 ^2 m^2 v^4} = \sigma\]so the collision frequency is

\[\nu_{ei} = n \sigma v = \frac{n e^4}{16 \pi \epsilon_0 ^2 m ^2 v^3}\] \[\rightarrow \eta = \frac{m}{n e^2} \nu_{ei} = \frac{e^2}{16 \pi \epsilon_0 ^2 m v^3}\]For Maxwellian electrons,

\[\eta \approx \frac{\pi e^2 m^{1/2}}{(4 \pi \epsilon_0)^2(k_b T_e)^{3/2}}\]Classical Resistivity #

Plasma undergoes numerous small-angle Coulomb collisions as well. Their cumulative effect ends up being larger than that due to large-angle collisions. Spitzer proposed that the temperature dependence should be scaled by a factor \( \ln \Lambda \) to account for these collisions:

\[\eta \approx \frac{\pi e^2 m^{1/2}}{(4 \pi \epsilon_0)^2(k_b T_e)^{3/2}} \ln \Lambda\]where \( \ln \Lambda \) is the Coulomb logarithm, and is \( \sim 10-20 \) for most plasmas.

For \( k_b T_e = 100\text{eV} \), \( \eta \sim 5 \cdot 10^{-7} \Omega \text{m} \), which is similar to that of stainless steel.

Physical Meaning #

For \( B = 0 \) and \( T = 0 \), in steady state

\[m_e \dv{\vec v}{t} = - e n E + R_{ei} =0\]From before, \( R_{ei} = \eta e^2 n^2 (\vec v_i - \vec v_e) = \eta e \vec J \), so we’ve recovered Ohm’s law and we can feel a bit better about our choice of \( \eta \) as the resistivity:

\[\vec E = \eta \vec J\]It is interesting to note that the resistivity we just wrote down is independent of density! That’s very different from what we usually see from resistivity. The current \( \vec J \) does not depend on the number of charges. Intuitively, this is because the increase in \( \vec J \) due to \( n_e \) would be offset by higher drag (\( \nu_{ei} \)).

Note that the resistivity is proportional to the electron temperature to the -3/2 power

\[\eta \sim T_{e} ^{-3/2}\]The collisional cross-section reduces with the electron temperature. High-temperature fusion plasmas are “collisionless”

Ohmic heating (\( \eta J^2 \sim I^2 R \)) is not an effective way to heat plasmas at high temperatures, since the resistivity drops off so quickly with temperature.

Runaway Electrons / Dreicer Field #

Note that \( \nu_{ei} \sim \frac{1}{v^3} \).

\[\nu_{ei} = \frac{n e^4}{16 \pi \epsilon_0 ^2 m^2 v^3}\]So faster electrons have fewer collisions, and lower resistivity. The high-speed tail of \( f(\vec v_e) \) carries most of the current. This has an interesting consequence when an electric field is applied: A phenomenon known as electron runaway can occur. A few electrons which happen to be moving fast in the direction of \( - \vec E \) when the field is applied will have gained so much energy before encountering an ion that they can make only a glancing collision. This allows them to pick up more energy from the electric field and decrease their collision cross section even further. If \( \vec E \) is large enough, the cross section falls fast enough that the runaway electrons never make a large-angle collision. They form an accelerated electron beam population, detached from the main body of the distribution.

We can estimate the maximum electric field \( \vec E \) that the plasma can sustain under steady-state, by combining the steady-state equation with resistivity equation.

The Dreicer field is

\[E_D = \left( \frac{e}{\lambda_D ^2} \right) \ln \Lambda\]However, in reality, plasmas can sustain \( |E| \gg E_D \). This suggests that the resistivity due to collisions, which decreases with \( |v| \) is supplemented by additional resistivity that has not been identified. This is “anomalous resistivity”. Low-frequency waves (\( \omega < \omega_c \) could supply this additional resistivity.)

Single Fluid MHD and Generalized Ohm’s Law #

Earlier we considered the 2-fluid model with the electron and ion populations considered separately as fluids that can “co-flow” together. For the problem of diffusion in a fully ionized plasma, it is simpler to work with the combined velocity \( \vec v_i - \vec v_e \) than to work with \( \vec v_i \) or \( \vec v_e \) separately. We define the combined center of mass density \( \rho \) and velocity \( \vec v \):

\[\rho = n_i m_i + n_e m_e = n(m_i + m_e) \approx n m_i\] \[\vec v = \frac{n_i m_i \vec u_i + n_e m_e \vec u_e}{n_i m_i + n_e m_e} \approx \vec u_i + \frac{m_e}{m_i} \vec u_e\]\[p = p_e + p_i \] \[\vec J = n e (\vec v_i - \vec v_e)\]

If we ignore the anisotropic stress tensor terms (assuming isotropic temperature), then the momentum equation is

\[n (m_i + m_e) \left[ \pdv{}{t} (m_e \vec u_e + m_i \vec u_i) + \left( \frac{m_e \vec u_e \cdot \grad \vec u_e + m_i \vec u_i \cdot \grad \vec u_i}{m_i + m_e} \right) \right] = \vec J \cross \vec B - \grad (p_e + p_i)\]Using the MHD assumptions, this simplifies to:

\[\rho \left( \pdv{\vec v}{t} + \vec v \cdot \grad \vec v \right) = \vec J \cross \vec B - \grad p\]Compare this with the fluid Euler equation

\[\rho \left( \pdv{\vec v}{t} + \vec v \cdot \grad v \right) = \rho \vec g - \grad p\]If we ignore the convection term and simplify, we get the Generalized Ohm’s Law

\[m_e \pdv{\vec J}{t} = \vec E + \vec v \cross \vec B - \eta \vec J + \frac{\grad p_e - \vec J \cross \vec B}{ne}\]The diamagnetic drift term \( \grad p_e / ne \) and the Hall drift term \( \vec J \cross \vec B / n e \) are typically much smaller than the other terms. If we disregard them, we get the usual form of the generalized Ohm’s law:

\[\vec E = \vec v \cross \vec B = \eta \vec J\]Diffusion in Fully Ionized Plasma #

From the MHD equations, for steady state (\( d \vec v/ dt = 0 \))

\[\vec J \cross \vec B = \grad p\] \[\vec E + \vec v \cross \vec B = \eta \vec J\]In the parallel direction where there is no contribution from \( \vec B \), we just get Ohm’s law

\[E_\parallel = \eta J_\parallel\]In the perpendicular direction:

\[\vec E \cross \vec B + (\vec v_\perp \cross \vec B) \cross \vec B = \eta_\perp \vec J \cross \vec B = _\perp \grad p\] \[- \vec B \cross (\vec v_\perp \cross \vec B) = - (B^2 v_\perp ^2 - \cancel{(\vec B \cdot \vec v_\perp)} \vec B)\]

\[\rightarrow \quad \vec v_\perp = \underbrace{\frac{\vec E \cross \vec B}{B^2}}_{\vec E \cross \vec B \text{ drift}} - \underbrace{\frac{\eta_\perp}{B^2} \grad p}_{\text{Pressure gradient diffusion}}\]The diffusion flux along the pressure gradient direction is

\[\Gamma_\perp = n \vec v_\perp = - \frac{n \eta_\perp (k_b T_e + k_b T_i)}{B^2} \grad n\]Compare with Fick’s law \( \Gamma = - D \grad n \), so the classical diffusion coefficient for a fully ionized gas is:

\[D_\perp = \frac{\gamma_\perp n \sum k_b T}{B^2}\]Note that \( D_\perp \sim 1 / B^2 \), same as a weakly ionized plasma. Since \( \eta \sim (k_b T)^{-3/2} \), \( D_\perp \) decreases with increasing temperature in a fully ionized gas. This is the opposite from the case with a partially ionized gas, because of the velocity dependence of the Coulomb cross section.

Diffusion is automatically ambipolar in a fully ionized gas (as long as like-particle collisions are neglected). \( D_\perp \) is the coefficient for the entire fluid; no ambipolar electric field arises, because both species diffuse together at the same rate. This is a consequence of the conservation of momentum in ion-electron collisions.

Bohm Diffusion #

The laboratory verification of the \( 1/B^2 \) dependence of \( D_\perp \) in a fully ionized plasma never came throughout the 1960’s. Instead, we saw \( B^{-1} \) instead of \( B^{-2} \) scaling, and the decay was found to be exponential rather than reciprocal with time. Bohm gave a semi-empirical formula

\[D_\perp = \frac{1}{16} \frac{k_b T_e}{e B} \equiv D_B\]This actually held for a surprising number of different experiments. Diffusion that follows this pattern is called Bohm diffusion.

Possible explanations:

- Magnetic field errors, and asymmetries can cause electron transport without collisions

- Asymmetric \( \vec E \) field can result in \( \vec E \cross \vec B \) drifts that can have components perpendicular to the wall

- Oscillating electric fields from wave instabilities can result in random fluctuations, causing collisionless random-walk due to \( \vec E \cross \vec B \) drifts.

Stability and Instability #

What drives plasma waves? #

So far, we have largely considered homogeneous, uniform plasmas with small perturbations caused by external forcing. If a plasma is completely uniform and homogeneous, then there is no free energy and it must be in the highest entropy state (e.g. Maxwellian distribution). However, most lab/space plasmas might be in equilibrium but can be driven unstable if there is free energy available which leads to wave generation within the plasma. Stability decreases free energy and drives the system towards thermodynamic equilibrium.

Classification of Instabilities #

Streaming Instabilities #

These are the majority of the instabilities we covered in this course. Ion acoustic instability and two-stream instability are both examples of streaming instabilities.

- Beam/current driven

- Relative drift energy (oscillation energy)

Rayleigh-Taylor instabilities #

This sort of instability is well-known in the area of fluid dynamics.

- Density gradient present in the plasma

- Non-electromagnetic, external force initiates the instability

Universal instabilities #

- Confined plasma always has plasma pressure that tends to expand the plasma

- Expansion energy can drive waves

Kinetic instabilities #

- Anisotropic velocity distribution, temperature anisotropies, etc. can cause instability. Eg Weibel instability.

Two-stream Instability #

- Consider the problem from the ions’ reference frame (stationary ions)

- One or multiple electron beams/streams present (2-stream, bump-on-tail)

- \( \vec B = 0 \)

- If electron stream is a beam, \( T = 0 \rightarrow p = 0 \)

Use perturbations in momentum equations, continuity and Poisson equations to get dispersion relation.

From \( D(\omega, k) = 0 \) note that complex-pair solutions of \( \omega \) for some \( k \) always appear as conjugate pairs.

One of the roots has \( \omega_i > 0 \), so instability. In this case, long-wavelength oscillations become unstable.