Collisions#

If \( \Lambda \) is large, then small-angle scattering dominates.

\[\nu = \frac{n}{2 \pi \epsilon_0 ^2} \frac{ e^4}{m^2 v_0 ^3} \ln \Alpha \propto \frac{n}{T^{3/2} m^{1/2}}\]Paschen curve for breakdown#

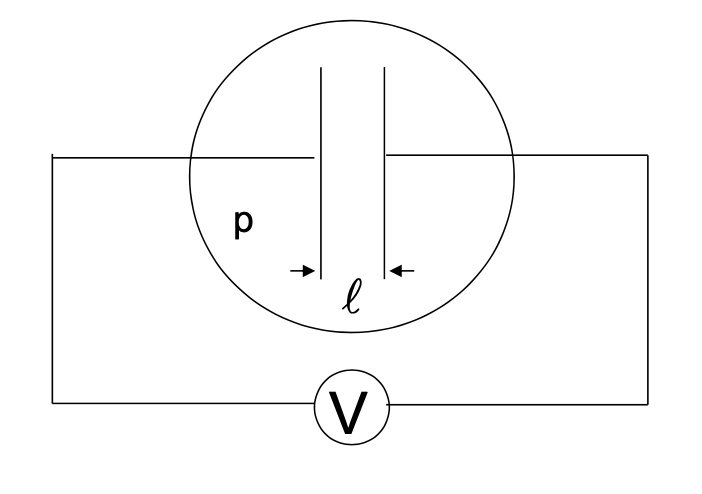

Say we have two large parallel plates

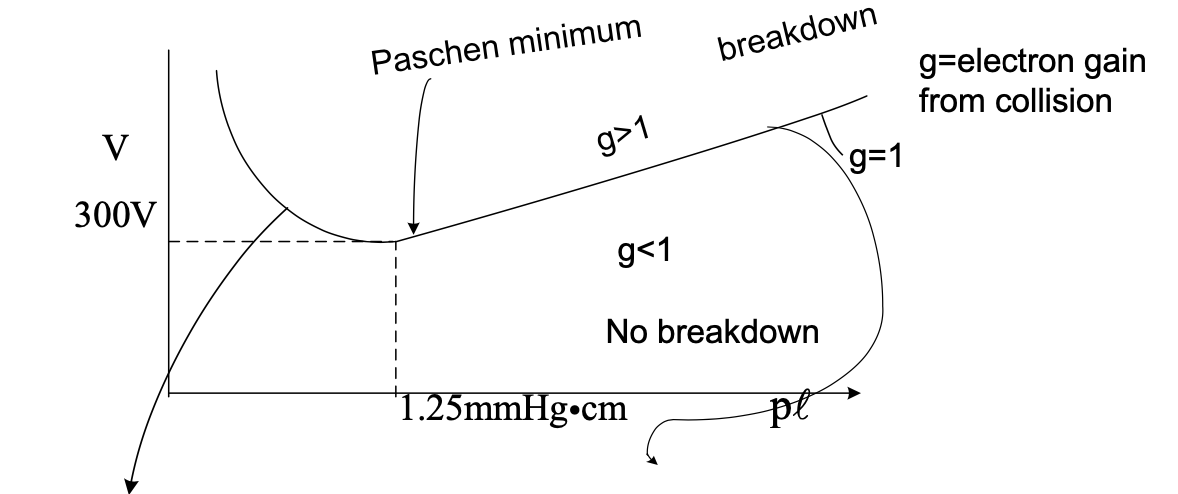

You can stay on the g=1 curve by putting a large resistor on your power supply, so it’s always running like it’s about to break down. Neutral-dominated plasma (neutral resistance).

To the left of the Paschen minimum, the spacing is less than the mean free path. There are surface losses. Electron loss to wall.

To the right of the Paschen minimum, there’s a fairly linear region with

- Local losses

- There is a certain \( \Delta V \) required between collisions that must be large enough to generate another electron before the electron is lost (\( l \) = spacing between the plates, \( l_{mfp} \) = mean free path

If you solve,

\[\Delta V = \frac{V}{l p} \cdot \text{const.}\] \[V = p l \left( \frac{\Delta V}{\text{const.}} \right) = p l \cdot \text{const.}\]\( g = 1 \) is used for voltage regulation.

Definition of Plasma#

Some basic criteria for plasma are

\[L \gg \lambda_D \qquad \text{ (neutral plasma) }\] \[\Lambda \gg 1 \qquad (\omega_{pe} \gg \nu_{ei}\] \[\nu_{en} < \omega_{pe} \quad \text{(if neutrals)}\]The collision frequencies have the following meanings:

- \( \nu_{ei} \) - Electron momentum loss rate on ions. Used in resistivity.

- \( \nu_{ee} \) Electron energy exchange rate with electrons. In other words, if you do something to the electrons this is how long it will take to get back to Maxwellian. Same order as \( \nu_{ei} \)

- \( \nu_{ii} \) Ion energy exchange rate with ions

- \( \nu_{ie} \) Electron energy exchange rate between electrons and ions. It’s about the same as ions slowing down in electrons: \( \approx \frac{m_e}{m_i} \nu_{ee} \). For fusion to work, need confinement times longer than this time.

Electrical Resistivity#

Place a plasma of density $n$ in an electric field (generated by voltage difference V). Electrons accelerate in one direction and ions in the other

\[\Delta p = F \cdot \Delta t\]Electrons and ions both get accelerated then collide and both stop since they had equal and opposite momentum

\[\Delta w = F \cdot \text{distance}\]The energy transfer will be much higher for the electrons because of their lower mass. So the electrons carry the current and receive ohmic heating for the resistive part of impedance

\[\langle m_i v_i \rangle = - \langle m_e v_e \rangle \rightarrow v_e \gg v_i\]The approx current is given by the drift velocity \( v_d \) by disregarding the velocity of the ions:

\[j = - n e \langle v_e \rangle + n e \langle v_i \rangle \approx - n e \langle v_e \rangle = |n e v_d|\]Identifying the resistivity with Ohm’s law

\[E = \eta j\]The force on the electrons is the rate at which momentum is lost by the electrons, which is the drift velocity times the electron-ion collision rate:

\[F_{elec} = E e = m v_d \nu_{ei} = \text{momentum loss rate}\] \[\rightarrow \eta j = E = \frac{m_e \nu_{ei} n e v_d}{n e^2}\] \[\rightarrow \eta = \frac{m_e \nu_{ei}}{n e^2}\]Recall the collision frequency

\[\nu_{ei} = \frac{n}{2 \pi} \frac{e^4}{\epsilon_0 ^2 m^2 v_0 ^2} \ln \Lambda\] \[\eta = \frac{m_e}{n e^2} \frac{n}{2 \pi \epsilon_0 ^2} \frac{Z_{eff}}{m_e ^2} \frac{e^4}{v^3 _0} \ln \Lambda\]The velocity is given by the electron thermal speed

\[v_0 ^3 \propto \left( \frac{ T_e}{m_e} \right) ^{3/2}\]The densities cancel and we can plug in some values

\[\eta = 5 \cdot 10^{-5} \frac{\ln \Lambda}{T_e ^{3/2}} \qquad \text{(Hydrogen)}\]Magnetic Decay Time#

The magnetic decay time for parallel current. For current parallel to the magnetic field, the curl of B is just some multiple \( \lambda \) of B:

\[\curl B = \lambda B = \mu_0 j = \mu_0 \frac{E}{\eta} \rightarrow E = \frac{\lambda \eta B}{\mu_0}\] \[\curl E = - \pdv{B}{t}\] \[\rightarrow \curl \frac{\eta \lambda}{\mu_0 } B = - \pdv{B}{t}\]This tells you the rate of decay of the magnetic field when you have helicity. The relevant timescale of the decay is

\[\frac{\eta \lambda^2 B}{\mu_0} = - \dv{B}{t} \rightarrow \tau = \frac{\mu_0}{\eta \lambda^2}\]Thermal Conductivity#

Consider a region of space where we have a hot side and a cold side. There is a heat flux \( Q \) flowing from the hot to the cold side

\[Q = \frac{\text{power}}{\text{area}}\]The thermal conductivity \( \kappa \) is defined by

\[Q \equiv - \kappa \pdv{T}{z}\]If the energy/particle going up / going down is \( \varepsilon \)

\[Q = \varepsilon _0 n_{down} v_{down} - \varepsilon _+ n_{up} v_{up}\]For mass conservation we must have

\[n_{down} v_{down} = n_{up} v_{up} = nv\] \[Q = \varepsilon _0 n v - \varepsilon_+ nv\]If we’re calculating the heat flux at some position \( z \) and the mean free path is \( l \) then particles come from about a mean free path distance. The energy dependence on \( z \) is given as \( \varepsilon(z) \)

\[Q \approx n v \left[ \varepsilon (z - l) - \varepsilon(z + l) \right]\] \[\rightarrow Q \approx n v \left[ \left(\varepsilon (z) - l \pdv{\varepsilon}{z}\right) - \left(\varepsilon(z) + l \pdv{\varepsilon}{z}\right) \right]\] \[\approx - n v l \pdv{\varepsilon}{z}\]The Maxwell-Boltzmann energy of the particles is

\[\varepsilon (z) = k T(z)\] \[Q \approx - n v l k \pdv{T}{z}\] \[\kappa = knv l_{mfp}\]Now we plug in the mean free path, assuming \( l_{mfp} \ll z_0 \) (where \( z_0 = \) plasma size.

\[l_{mfp} = v t_c = \frac{v}{\nu} \approx \frac{(k T)^{1/2} T^{2/3} m^{1/2}}{m^{1/2} n \ln \Lambda}\] \[\rightarrow \kappa \sim \frac{T^{5/2}}{m^{1/2} \ln \Lambda} \sim \frac{T^{5/2}}{m^{1/2}} \]If there is no magnetic field (or we’re looking parallel to the field) then

\[\kappa \propto \frac{ T^{5/2}}{m^{1/2}}\]There’s a thing called the conductivity of the Lorentz gas (ions are infinitely massive)

\[\kappa_{lorentz} \approx 4.67 \cdot 10^{-12} \frac{T^{5/2}}{Z \ln \Lambda}\] \[\kappa_{Z=1} \approx 4.4 \cdot 10^{-13} \frac{T^{5/2}}{Z \ln \Lambda}\]What happens when we add a magnetic field? \( B = B_0 \)

\[l_{mfp} \rightarrow r_g\]\( r_g \) = radius of gyration = \( \frac{v}{\omega} \)

\[r_g = \frac{v}{\omega} \qquad l_{mfp} = v \tau_c \qquad \tau_c = \frac{1}{\nu}\] \[\frac{r_g}{l_{mfp}} = \frac{v}{\omega} \frac{1}{v \tau_c} = \frac{1}{\omega \tau_c}\rightarrow \kappa\]where \( \kappa \) is reduced by a factor \( \frac{1}{\omega \tau_c} \) compared to the non-magnetized plasma. The energy is now transmitted over a shorter distance, but it also has a lower fluence. The particles move a distance \( r_g \) over every time \( \tau_c \), so the transport velocity is reduced

\[v \rightarrow \frac{r_g}{\tau _c} \rightarrow \text{ reduced by } \frac{r_g}{v \tau_c} = \frac{1}{\omega \tau} \quad (v = \omega r_g)\]That’s an additional reduction by \( \frac{1}{\omega \tau} \), so

\[\kappa_B \approx \kappa_0 \left( \frac{1}{\omega \tau}\right) ^2\]What is the mass dependence

\[\kappa_B \rightarrow \frac{1}{m^{1/2}} \left( \frac{m}{m^{1/2}} \right) ^2 = m^{1/2}\]In the cross-field direction, ions dominate the cross field thermal conduction

\[\kappa _\perp \approx \kappa_{\parallel, e} \left( \frac{1}{\omega_{ce} \tau_{ee}} \right)^2 \left( \frac{m_i }{m_e} \right) ^{1/2} \]or

\[\approx \kappa_{\parallel, i} \left( \frac{1}{\omega_{ci} \tau_{ii}} \right) \propto m^{1/2} T^{5/2} \left( \frac{n}{B T^{3/2}} \right) ^2 \propto \frac{m^{1/2} n^2}{B^2 T^{1/2}}\]To get real numbers, use Spitzer

\[\kappa_\perp = 1.6 \cdot 10^{-40} \frac{A_i ^{1/2} n^2 \ln \Lambda}{T^{1/2} B^2}\]where \( T \) is in \( eV \), \( B \) is in Tesla, \( n \) is in \( m^{-3} \), \( Z \) is the atomic charge, and \( A_i \) is the atomic mass number

\[\eta = \frac{b}{T^{3/2}} \qquad b = 5.2 \cdot 10^{-5} Z \ln \Lambda\]Ohmic heating balancing cross field thermal conduction#

Let’s consider a region of plasma (radius \( a \) and length \( L \) and estimate the parameters required to achieve a balance between ohmic heating and the cross-field thermal conduction.

The thermal conduction power is

\[Q 2 \pi a L\]The ohmic heating is

\[\eta j^2 \pi a^2 L\] \[\kappa \frac{T}{a/2} = \eta \frac{\lambda^2 B^2 a}{\mu_0 ^2 2} \qquad \curl B = \lambda B = \mu_0 j\] \[\frac{C n^2 T}{T^{1/2} B^2} = \frac{b B^2}{T^{3/2} 2^2 \mu_0 ^2} \lambda ^2 a ^2 \qquad \kappa_\perp = C \frac{n^2}{T^{1/2}B^2} \qquad \eta = \frac{b}{T^{3/2}}\] \[\beta ^2 \equiv \frac{(2 k n T)^2}{(B^2/2 \mu_0)^2} = 4 k^2 \frac{b}{C} \lambda ^2 a^2 \]where \( \beta \) is the ratio of the plasma pressure \( p = 2 n k T \) (the factor of 2 accounts for both species in the plasma) to the magnetic pressure \( p_{mag} = B^2 / 2 \mu_0 \).

For \( Z = 1 \) and \( A_i = 2 \),

\[\rightarrow \beta = 0.15 \lambda a\]\( \lambda a \approx 2.4 \) for spheromak, but only \( \approx 0.5 \) for tokamak.

Axial thermal conduction cools ohmic heating#

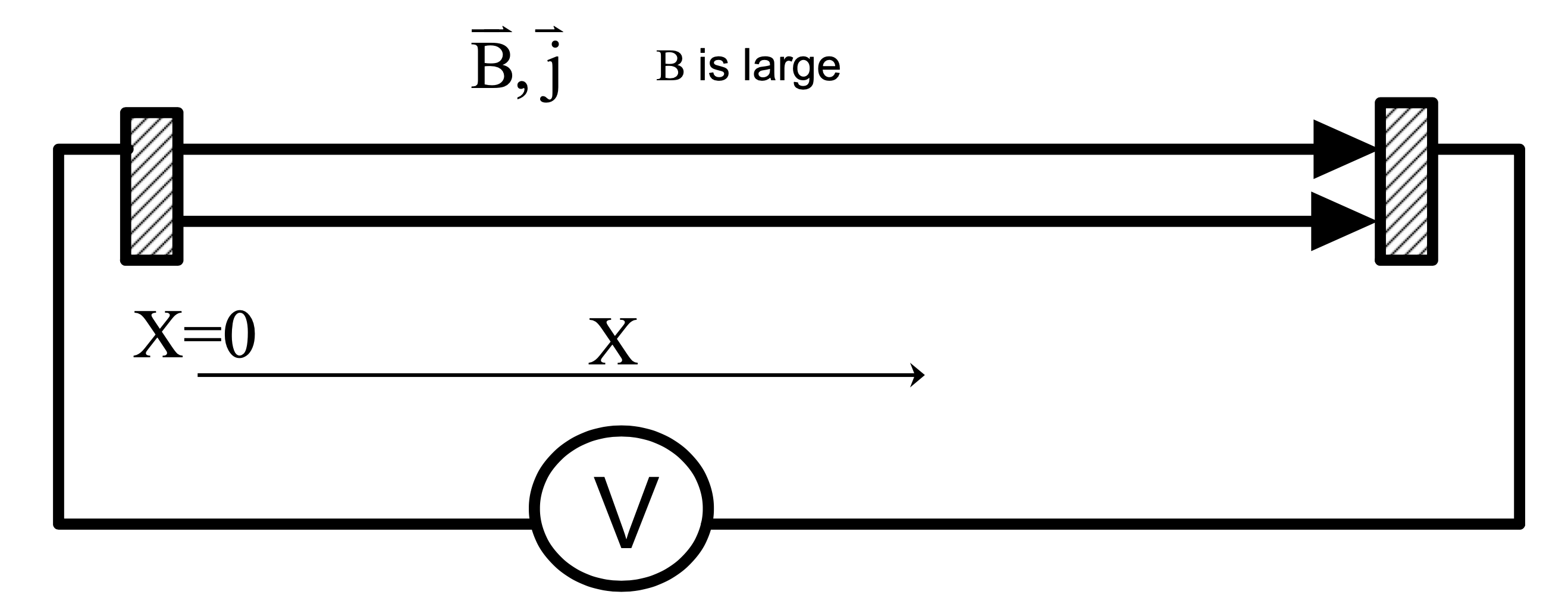

Consider a voltage applied parallel to the magnetic field

Assume that the length is short enough that cross field transport is small compared to axial loss

\[Q = - \kappa \dv{T}{X} \qquad \kappa \approx A T^{5/2}\]Let’s just ignore the temperature dependence of \( \Lambda \) (since it is slowly varying). Also assume that a current density \( j \) is being driven and the system is in a steady state.

\[\dv{Q}{X} = \eta j^2 \qquad \eta = \frac{b}{T^{3/2}}\] \[b = 5.2 \cdot 10^{-5} Z \ln \Lambda\]Make things dimensionless by normalizing \( X \) by \( \sqrt{b/A} j/T_0 ^{5/2} \), \( q \) by \( -Q/\sqrt{Ab}T_0 j \) and \( T \) by \( T_0 \).

\[x = X \sqrt{\frac{b}{A}} \frac{j}{T_0 ^{5/2}}\] \[q = \frac{-Q}{T_0 j \sqrt{Ab}}\] \[T = \frac{T}{T_0}\] \[\rightarrow Q = - A T^{5/2} \dv{T}{X}\] \[\dv{Q}{X} = \frac{b}{T^{3/2}} j^2\] \[- \frac{Q}{A T^{5/2}} = \dv{T}{X} \]Replacing the dimensionless quantities,

\[\rightarrow \frac{q}{T^{5/2}} = \dv{T}{x}\] \[\dv{Q}{X} = \eta j^2 = \frac{b}{T^{3/2}} j^2\] \[\rightarrow - \dv{q}{x} = \frac{1}{T^{3/2}}\]Write equation in terms of \( T_0 \)

\[\sqrt{Ab} T_0 j = - Q\]This is \( Q \) into one electrode

Power per unit area going into the wall is equal to power per unit area in terms of the voltage

\[\sqrt{Ab} T_0 j = \frac{V j}{2}\] \[\sqrt{4AB} T_0 = V\] \[T_0 = \frac{V}{\sqrt{4Ab}} \approx \frac{V}{\sqrt{6}}\]True for anything without losses across the electrodes.

Viscosity#

The shear force is written as

\[P_{yx} = - \mu \pdv{u_x}{y}\]Viscosity is a force per unit area with the force parallel to the surface. It tends to make things want to go the same velocity. It comes about by particles exchanging across the surface

\[\mu_{B=0} \propto \frac{T^{5/2} A_i ^{1/2}}{4Z\ln \Lambda}\] \[\mu_B \propto \frac{n_i ^2 Z^2}{T^{1/2} B^2} A_i ^{3/2} \ln \Lambda\]