Spectroscopic Measurements#

Plasma Self-Emission#

Plasmas emit light (electromagnetic radiation) over a broad range of wavelengths. This can be from the X-ray to UV to visible to IR. The emission depends on the plasma constituents, magnetic field, and plasma properties \( n_e, T_e, T_i, \vec v_i \). We should be able to analyze the self-emission to provide a measurements of these properties. These measurements are both rich in information, and completely non-perturbing. Unfortunately, extracting plasma properties from measurements can be extremely complicated, since the emission is influenced by all of these effects together.

Free Electron Emission#

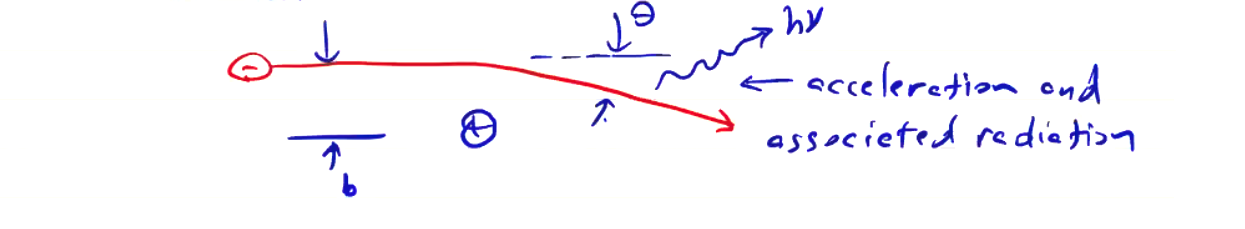

The primary form of free electron radiation comes from Bremsstrahlung, which is the radiation resulting from the electron’s Coulomb interaction with an ion. An electron passing by an ion is deflected through an angle \( \theta \) and radiation is emitted as a result. The degree of reflection depends on the electron’s energy and the impact parameter. For a given electron temperature, the impact parameter spans a range up to \( \lambda_D \) and produces a broadband spectrum of radiation.

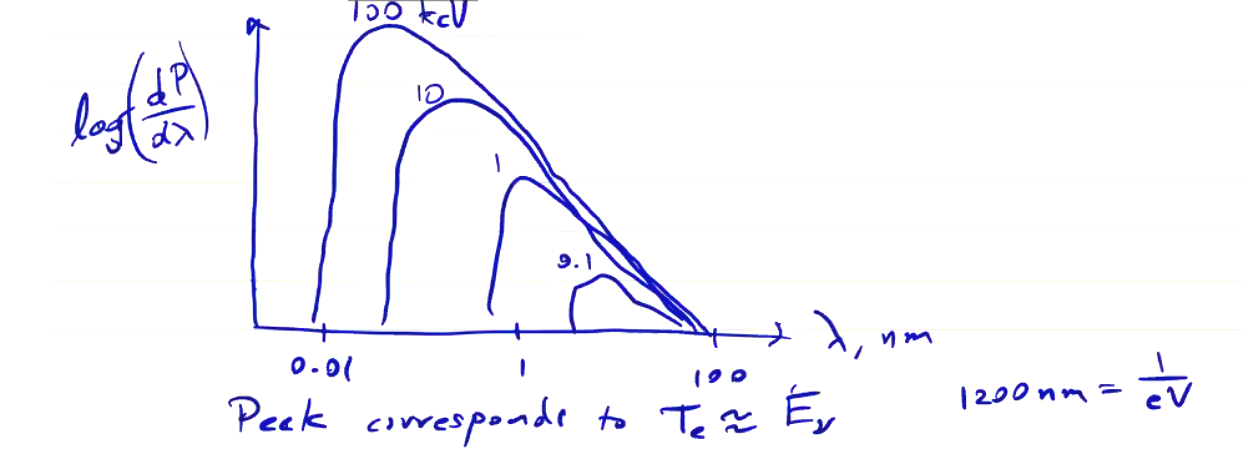

Considering plasma temperatures in the range \( T_e = 10 eV \sim 10 keV \), this emission will be in the soft x-ray range (\( \lambda = 0.1 \sim 100 nm \)).

Blackbody radiation is another major source of free electron emission in broadband. Thermal bodies will radiate energy according to

\[B(\nu) = \frac{\nu^2}{c^2} \frac{h \nu}{e^{h \nu - T} - 1} \sim \frac{\nu^2 T}{c^2} \quad (\text{for low } \lambda)\]

If we plot the intensity change with frequency, we find that the peak will be near the electron temperature

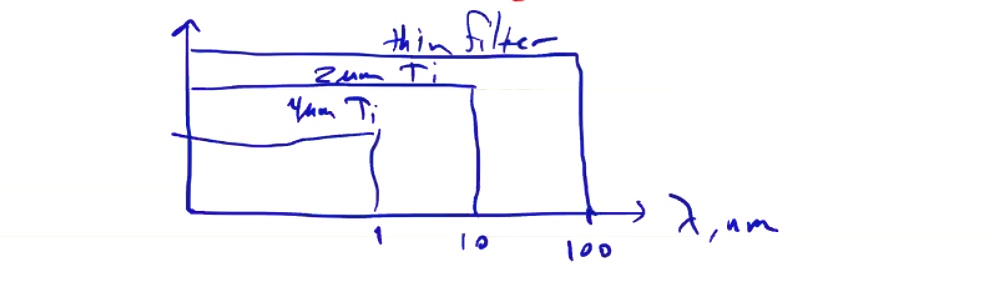

\[T_e \approx E_\nu\]We can measure the x-ray spectrum using filtered detectors. The penetration depth of x-rays depends on their energies, so one can set up a set of detectors behind filters of various thicknesses. With multiple detectors and multiple thicknesses of filter, you can piece together the spectrum. Remember that all photons with high enough energy will pass through the filter, so the resulting ideal acceptance might look like the following:

Typical materials are metals like Ti, Al, Be, and Ni, and are chosen based on their transmission spectrum. Transmission spectra of real materials are not flat, so you have to convolve the filter transmission spectrum with what you’re measuring. Beryllium has a very nice smooth transmission spectrum in the soft x-ray range, but it is very toxic making it difficult to work with. As for the detectors themselves, they must be sufficiently sensitive to x-rays (not all detectors are). X-ray diodes (XRD) are useful, and photomultiplier tubes coupled with an x-ray scintillator are also useful.

We know that Bremsstrahlung radiation spectrum shape depends on \( T_e \). We can also look at the total Bremsstrahlung radiated power:

\[P_{Br} \approx 5 \cdot 10^{-37} Z_{eff} n_e ^2 T_e ^{1/2}\] where \[Z_{eff} \equiv \frac{\sum_{ions} n_e n_i Z_i ^2}{n_e ^2}\]

Charge neutrality lets us express \( Z_{eff} \) as

\[Z_{eff} = \frac{\sum_i n_i Z_i ^2}{\sum _i n_i Z_i}\]For a pure hydrogen plasma \( Z_{eff} \) is always 1. Impurities increase \( Z_{eff} \), so a measurement is useful to help identify impurity concentrations and resistivity. The measurement requires absolute calibration of the detector and spectrometer, so it’s a difficult one to obtain. We can improve the confidence by using corroborating measurements of \( n_e \) and \( T_e \) from other diagnostics.

Self-Emission from Bound Electrons#

Electrons still bound to the nucleus will emit radiation as they are excited by collisions, typically with free electrons, and then de-excite to a lower state. The quantum jumps between states produce photons of a well-defined energy, hence line radiation

\[E_i - E_j = h \nu_{ij}\]In a hydrogen plasma, line radiation is produced only from neutral hydrogen (not ionized). We use H-I to denote emission from the outer-most (I) electron of the hydrogen atom. We often look at impurities, which can be ionized to a higher degree. The emission profile is for a given electron temperature, assuming the ionization population is in thermal equilibrium with the rest of the plasma. For example, C-III indicates that the outer-most electron is the third least-bound, so both of the 2p electrons have been freed: \[C-III: \qquad 1s^2 2s^2 (2p^2)\] We can see that C-III is a Beryllium-like atom. C-V is another common one in high-temperature plasma, and is a Helium-like atom. In thermal equilibrium, the distribution of ions/atoms in any quantum state is given by

\[N_i \propto \exp \left( -\frac{E_i}{T} \right)\]and

\[\frac{N_i}{N_j} = \exp \left( - \frac{E_i - E_j}{T} \right) = \exp \left( - \frac{h \nu_{ij}}{T} \right)\]In general, state \( E_i \) can be degenerate, so we add a multiplier \( g_i \), \( g_j \) in front to correspond with the number of degenerate states. If in thermal equilibrium, that means that the de-excitation rate \( i \rightarrow j \) (emission) is equal to the excitation rate \( j \rightarrow i \).

If we assume that these are the only mechanisms involved, the plasma is said to be in coronal equilibrium. Assumption is valid for low-density plasmas, where we have

- no collisional/three-body de-excitation

- no radiative absorption (optically thin)

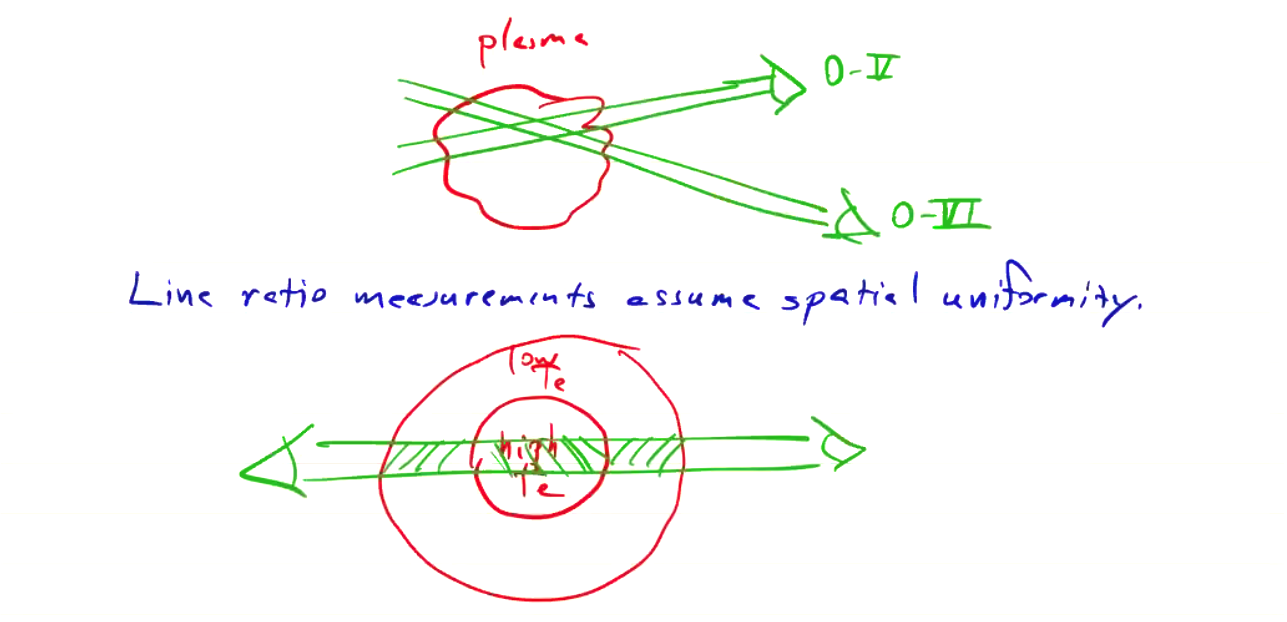

The line ratio measurements implicitly assume spatial uniformity

Doppler Broadening#

If the radiator is moving, the wavelength shifts according to the relative velocity between the radiator and the viewer.

\[\lambda_{obs} = \lambda_0 \left( 1 \pm \frac{\vec v_{i}}{c} \right)\]where \( \vec v_{i} \) is the component of the ion velocity towards the observer (spectrometer). Measurements of Doppler broadening are useful for making measurements of the bulk velocity of the plasma. Thermal vibrations will also result in a broadening of the line. The width of the broadening is related to the temperature

\[f(\nu) = \left( \frac{m_i}{2 \pi T_i} \right)^{3/2} \exp \left( - \frac{ \frac{1}{2} m_i (v - v_i) ^2}{T_i} \right)\]which gives spectral emissivity

\[e(\lambda) = E \left( \frac{ m_i}{2 \pi T_i \lambda_0 ^2} \right) ^{1/2} \exp \left[- \frac{(\lambda - \lambda_0 + v_i \lambda_0 / c)^2}{2 T_i \lambda_0 ^2/m_i c^2} \right] + B\]where \( E \) is the total emissivity and \( B \) is the background signal (e.g. broadband Bremsstrahlung).

\[\Delta \lambda_{FWHM} = 2 \lambda_0 \sqrt{ \frac{2 \ln (2) T_i}{m_i c^2}}\]